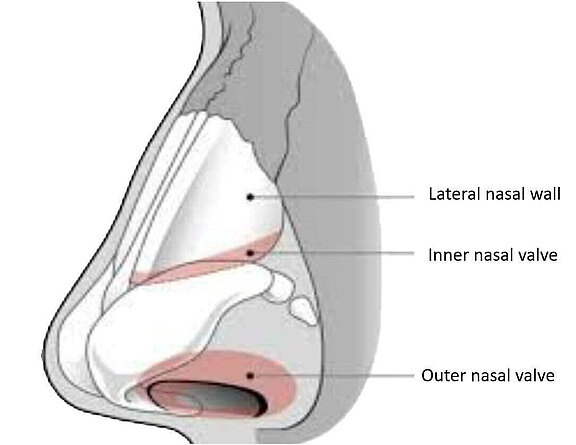

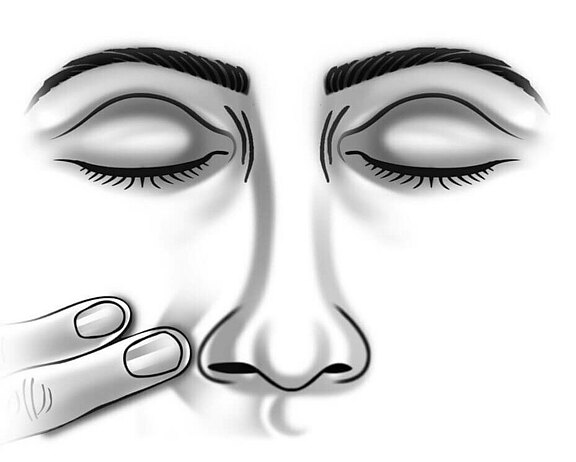

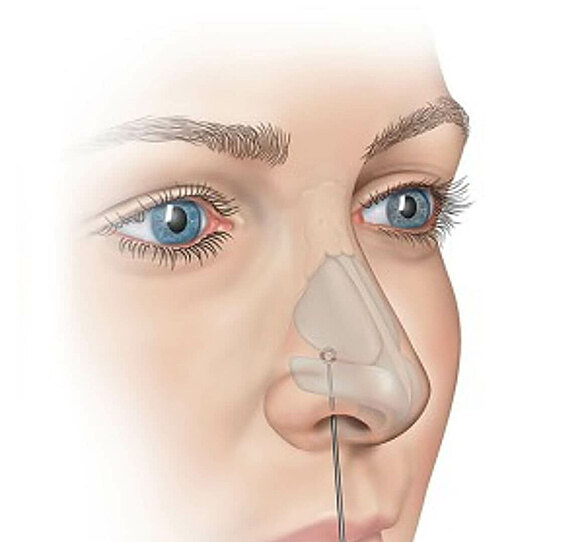

The reduced tension (tone) of the mimic muscles also leads to changes in the area of the nasal complex. Many patients are impacted by an elapsed "nasolabial fold". The nasolabial fold is a natural fold that begins on both sides of the nose next to the nostrils and usually ends at the corner of the mouth. With increasing age, a more prominent nasolabial fold is formed by a thickening of the cheek fat body and the overlying skin layer.[1] Due to the reduced activity of the facial musculature in facial nerve palsy, it increasingly flattens. Sometimes the entire nose is distorted. In addition, the inner and outer nasal valve (see Fig. 1) can collapse[2], as there is a loss of tension (loss of tone) of the nostril dilator (M. dilatator naris apicalis) and the adjacent soft tissue.[3] In particular, sinking of the inner nasal valves may have a negative effect on nasal ventilation, since this area already forms the narrowest part of the nasal cavity in healthy humans and causes 50% of the nasal airflow resistance.[4] In the case of nasal constriction, the cottle sign (see Fig. 2) and the modified cottle sign (see Fig. 3) may appear. In the former, a sideways (lateral) pull on the cheek leads to a subjective improvement in nasal airflow. The same effect can be observed with the modified cottle sign.[5] In the modified version, the nasal valve is supported from the inside. In addition, facial paralysis shows an increase in nasal mucociliary clearance, i.e. the self-cleaning mechanism of the nasal airways, on the non-paralysed side.[6] This could be caused by a compensation mechanism. For the therapy of nasal collapse, the insertion of a fascia lata sling is suitable.[7]

Figure 1

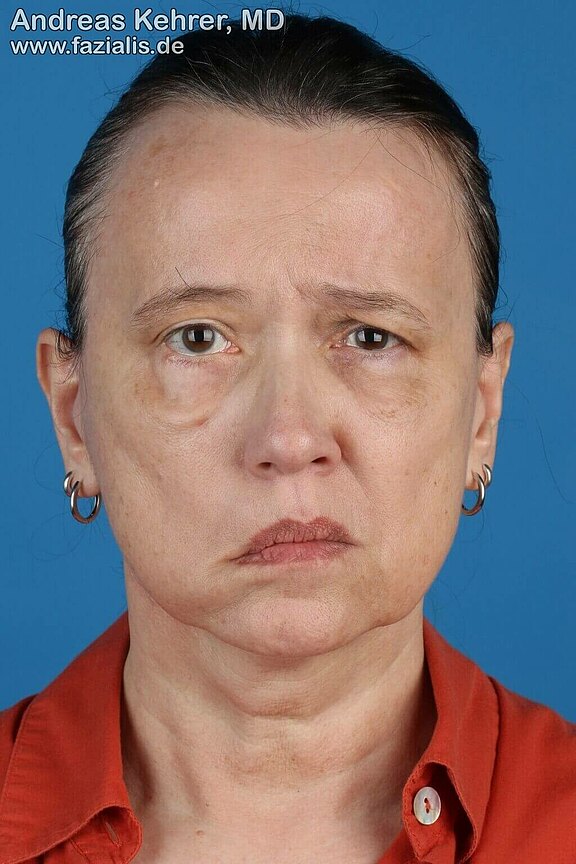

Before her operation, this 57-year-old facial paresis patient complained, in addition to other complaints, of significantly more difficulty breathing through her nose on the right side – the affected side of her face. Typically, muscle slackening leads to a collapse of the so-called inner nasal valve, i.e. the air passage inside the nose. As a result of a rejuvenation of the air flow during breathing through an internal nasal valve that is too narrow, there is increased resistance to nasal breathing: a one-sided nasal ventilation disorder develops. If one places a finger on the cheek directly next to the affected nostril and pulls the cheek tissue outwards during nasal breathing, the nasal valve opens, and nasal breathing is facilitated (positive Cottle sign). This can be remedies by the external insertion of autologous tissue in the form of a static suspension plastic. The connective tissue used keeps the inner nasal valve constantly open and greatly facilitates nasal breathing. The introduction of autologous tissue can be combined with nerve rearrangement, nerve transplantation and the transplantation of a functioning muscle. This procedure was performed on this patient, who was pleased with her significantly improved nasal breathing after the operation.

This 3D learning model from our friends at ANATOMYNEXT (www.anatomynext.com) illustrates the nose muscles. The M. procerus is responsible for the formation of the frown line together with the M. depressor suopercilii. In addition, the transverse part of the nasalis muscle (Pars transversa musculi nasalis) and the compressor narium serve to close the nostrils. The M. depressor septi nasi pulls parts of the nasal septum downwards (caudally) according to its name. The 3D learning model was created by our friends from ANATOMYNEXT (www.anatomynext.com), who enrich our site with their excellent 2D and 3D teaching models.

Source: Modified by author: Varedi P, Bohluli B. Contemporary Rhinoplasty Techniques, A Textbook of Advanced Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2015 Volume 2, Mohammad Hosein Kalantar Motamedi, IntechOpen, doi: 10.5772/59811. www.intechopen.com/books/a-textbook-of-advanced-oral-and-maxillofacial-surgery-volume-2/contemporary-rhinoplasty-techniques. Accessed on 09/03/2020. FIG. CC BY-SA 3.0. creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/.

Source: Stolovitzky P et al. A prospective study for treatment of nasal valve collapse due to lateral wall insufficiency: Outcomes using a bioabsorbable implant. The Laryngoscope 2018.doi:10.1002/lary.27242, FIG2, CC BY-SA 4.0, creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en.

Sources:

[1] Gosain AK, Amarante MT, Hyde JS, Yousif NJ. A dynamic analysis of changes in the nasolabial fold using magnetic resonance imaging: implications for facial rejuvenation and facial animation surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996 Sep;98(4):622-36. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199609001-00005. PMID: 8773684.

[2] Lindsay RW, Bhama P, Hohman M, Hadlock TA. Prospective evaluation of quality-of-life improvement after correction of the alar base in the flaccidly paralyzed face. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015 Mar-Apr;17(2):108-12. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2014.1295. PMID: 25554967.

[3] Park JY, Kim HJ et al. Lateral Nasal Valve Suspension: Nasal Valve Collapse with Facial Palsy. Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2011;54 (3): 239-241. doi:https://doi.org/10.3342/kjorl-hns.2011.54.3.239.

[4] Haight JS, Cole P. The site and function of the nasal valve. The Laryngoscope. 1983 Jan;93(1):49-55. DOI: 10.1288/00005537-198301000-00009.

[5] Mashkevich, G., & Azizzadeh, B. (2012). Adjunctive techniques in facial paralysis. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 23(4), 282–287.doi:10.1016/j.otot.2012.08.004

[6] Boynuegri S, Ozer S, Peksoy I, Açikalin A, Tuna E Ü, Dursun E, Eryilmaz A. Rhinoscintigraphic analysis of nasal mucociliary function in patients with Bell's palsy. Niger J Clin Pract 2016;19:359-63

[7] Hadlock TA, Cheney ML, McKenna MJ. Facial reanimation surgery. In: Nadol JB Jr, Mckenna MJ, editors. Surgery of the ear and temporal bone. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Philadelphia 2005. P461–472