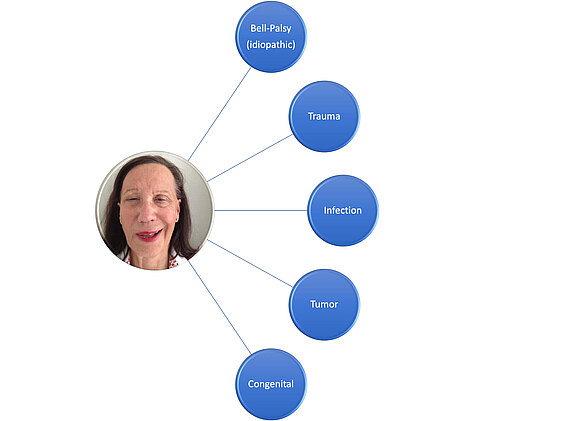

The epidemiology (from Greek "epidēmíā nósos" "disease spread over the whole people", lógos "doctrine") deals with the spread as well as the causes and consequences of diseases in the population. Etiology, on the other hand, deals with the causes for the development of a disease. Etiology and pathogenesis of facial paralysis (causes of facial palsy):

The prevalence (frequency of a disease or symptom in a population at a given time) of paralysis of the facial nerve has been studied in multiple studies and varies between 17 and 35 cases per 100000 population for all forms of paresis [1-5]. Studies from Great Britain and Canada showed an incidence (frequency of new cases in a certain period) of 13.1 to 20.2/100000 [6.7] for idiopathic (no known cause) facial paralysis Bell’s Palsy A 1975 study described the incidence of Bell’s Palsy in pregnancy as 45 / 100000 compared to 17/100000 in non-pregnant women. So far, no significant predilection concerning origin, sex or ethnicity could be determined [1,19]. Various studies [1,2,8-10] have shown that the risk of developing facial nerve palsy after Bell is highest between the ages of 15 and 45.

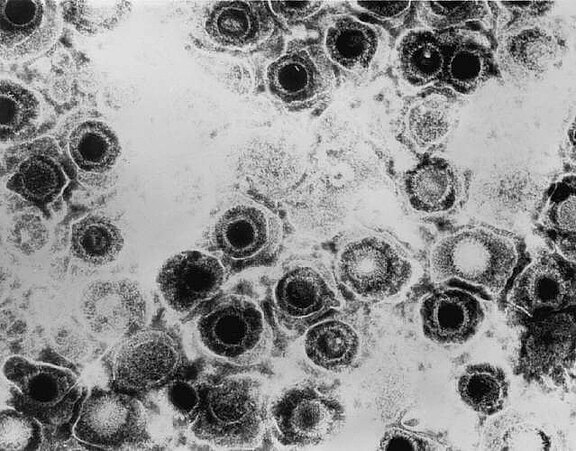

Bell’s Palsy, named after the Scottish surgeon Sir Charles Bell (1774-1842), is the most common form of idiopathic facial paresis. Women and men are equally affected, although the risk may be increased during pregnancy. The exact mechanism of damage has not been sufficiently researched. It is believed that inflammation (probably viral) leads to swelling of the nerve in the area of the passage through the cranial bone (Canalis n. facialis). The nerve fibres are damaged by compression and a resulting reduced flow of blood (see Pathophysiology) (11). Autoimmune reactions or the reactivation of a herpes simplex virus infection (HSV type 1) are suspected to trigger the inflammation. Residual symptoms can include facial weakness, synkinesis, tearing, and contracture.

Electron microscope image of a herpes simplex virus, type I. Infestation of the facial nerve can cause swelling via inflammation of the nerve (neuritis). In the narrow Canalis Facialis ("petrous bone canal"), very limited space conditions exist for the facial nerve. This causes damage to the nerves.

Source: Dr. Erskine Palmer, CDC, Transmission electron micrograph of herpes simplex virus. Some nucleocapsids are empty, as shown by penetration of electron-dense stain, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027 USA, 1981, phil.cdc.gov/PHIL_Images/08301998/00014/B82-0474_lores.jpg, accessed on 08/28/2020.

In the case of acute (recent) Bell’s Palsy, treatment with glucocorticoids is recommended. Possible regimes are: 10 days 2x25 mg prednisolone [12] or 5 days 60 mg prednisolone [13]. A combination with virostatic drugs is only recommended, in very severe cases [14]. Acute treatment should always be carried out by a specialist in neurology / ear, nose and throat medicine as soon as paresis occurs and is often carried out as part of a short inpatient stay in a clinic. Other causes, such as borrelliosis, are ruled out by laboratory tests and possibly lumbar puncture.

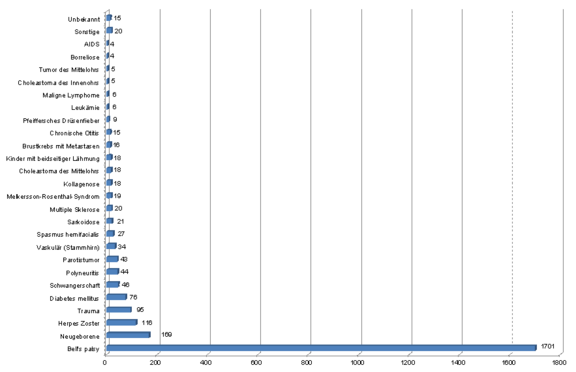

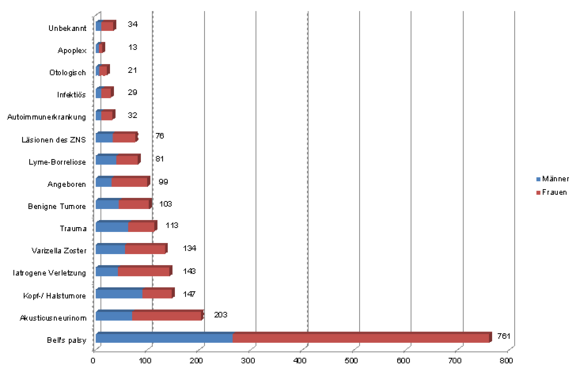

These studies must, of course, be viewed under the critical aspect that the data set used does not necessarily reflect a representative section of the total population. The patient base on which these clinical investigations are based is significantly influenced by the location and specializaation of the respective clinics and centres.

Nevertheless, the studies by Peitersen and Hohman et al. show that idiopathic facial paralysis (without a known cause or no scientifically proven pathomechanism known) represents the largest proportion of facial paresis after Bell (Peitersen: 66.19% and Hohman: 38.26%). Congenital pareses, traumas, infections and tumour diseases also play an important role.

Infections of the herpes zoster virus (shingles) in the head and neck area may lead to facial nerve palsy. Here in the picture the vesicles of the virus infection (painful, erythematous-vesicular rash) around and in the auditory canal (Herpes zoster oticus) are clearly visible. It is a direct infection of cranial nerves. If the facial nerve is also affected, it can lead to a loss of function with facial paralysis on the same side. This symptom complex is also called Ramsay-Hunt syndrome[15], named after the American neurologist James Ramsay Hunt (1874-1937). The disease, also known as Ramsay-Hunt neuralgia, may further be characterized by dysfunction of other cranial nerves. For instance, nerve pain (neuralgia) may also be a complication. Other common manifestations are hearing loss, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), dizziness, nausea, vomiting and nystagmus (uncontrollable, rhythmic eye movements).

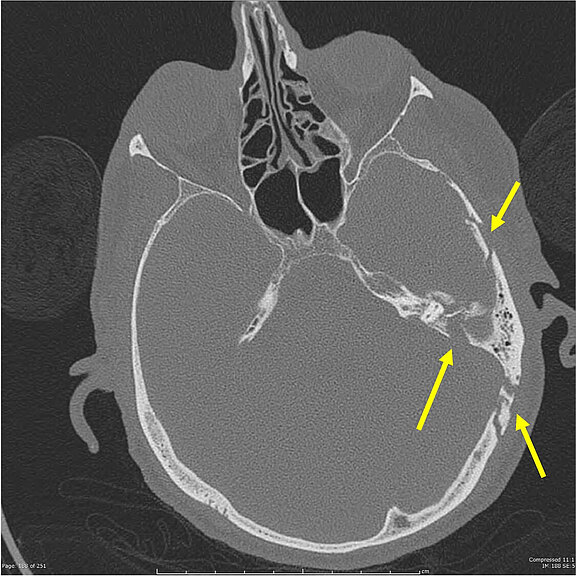

Source: Dr. Steve Lau, Radiopedia, Complex, comminuted temporal bone fracture, n.d., radiopaedia.org/cases/complex-comminuted-temporal-bone-fracture, accessed on 08/28/2020.

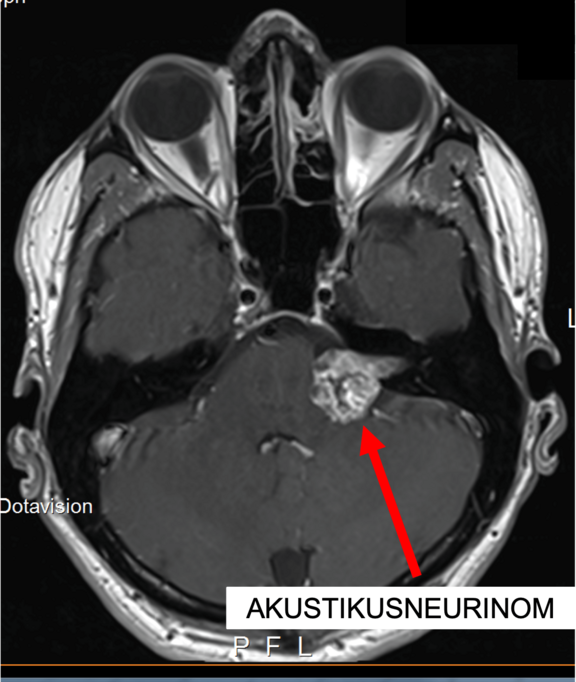

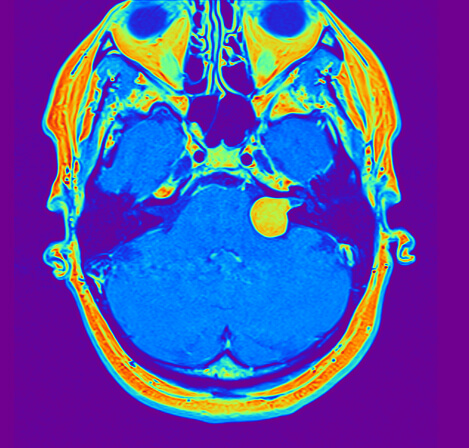

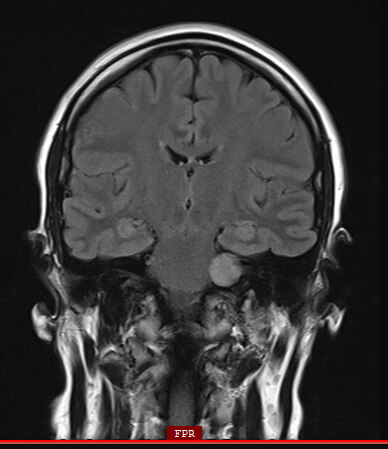

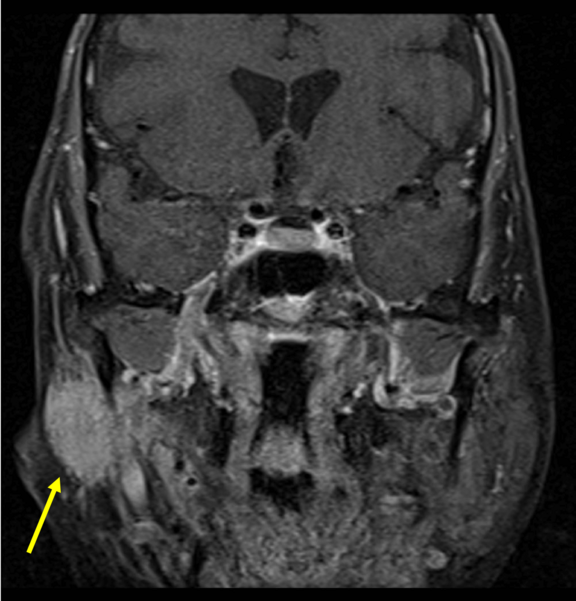

In this magnetic resonance tomography (MRT) cross-sectional imaging diagnosis, an acoustic neurinoma at the left skull base can be clearly identified as the cause of facial paralysis: the signal enhancement shows a tumour growing in a displacing manner (shown here in light) with an extension into the petrous bone (shown here in dark/black), through which the facial nerve also passes through a bony canal. The consequence of tumour growth is a compression of the facial nerve with the corresponding symptoms of complete or partial facial paralysis, depending on how many nerve fibres are affected.

Source: Modified by author: Ärztlicher Direktor Prof. Dr. med. Marcos Tatagiba, Neurochirurgie Uniklinikum Tübingen, Vestibularisschwannom, 72076 Tuebingen GER, n.d., www.neurochirurgie-tuebingen.de/de/spezialgebiete/akustikusneurinom/, accessed on 08/28/2020.

Processes outside the skull, but within the parotid gland (glandula parotis) can also cause functional disturbances of the facial nerve branch system. This MRI image shows an adenocystic carcinoma (yellow arrow). However, benign tumours of the parotid gland are much more common. The distribution of the parotid gland tumours is about 80% benign and 20% malignant. The most common benign salivary gland tumor is the pleomorphic adenoma. The second most common is the benign warthin tumor (cystadenolymphoma). Removal of the parotid gland (parotidectomy), according to international literature, causes permanent facial paralysis in only 2-6% of all cases [16]. Temporary nerve paralysis is observed in 25-60% of cases [17].

Source: Published as “Jto410”, Coronal fat-suppressed post gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted image showing and enhancing right parotid mass with perineural spread of tumor along the trigeminal nerve. In my clinical work as radiologist, 09/09/2013, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coronal_MRI_showing_right_parotid_adenoid_cystic_carcinoma_with_perineural_spread_of_tumor.jpg, accessed on 08/28/2020, CC BY-SA 3.0. creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0.

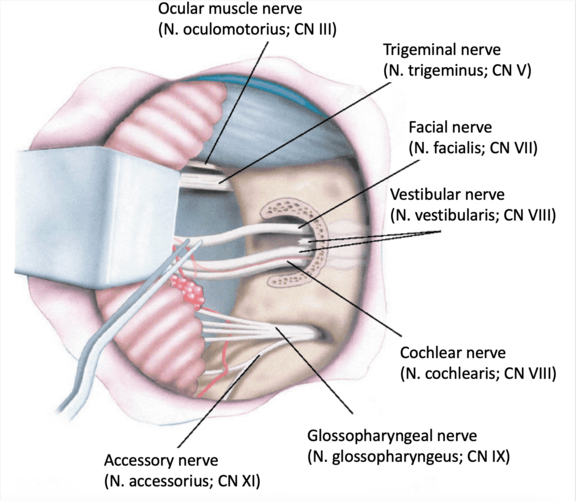

Like other tumors of the skull base, the acoustic neuroma grows in close proximity to various cranial nerves, which are shown here. If it is a larger tumor, it may encircle or encapsulate the cranial nerves. Either directly due to tumor growth or upon tumor removal, this may result in temporary or permanent functional limitations of the cranial nerves, including the facial nerve. If the nerves have to be removed at the same time as the tumor due to the size of the tumor, the result is a nerve gap with complete loss of the affected nerve with no prospect of primary nerve healing. This is referred to as "lack of continuity," which in the case of the facial nerve results in complete, flaccid facial paralysis. In these cases, nerve reconstruction should be planned at an early stage.

Möbius syndrome is characterized by congenital paralysis of the sixth and seventh cranial nerve.[18] The Möbius Syndrome is named after the German neurologist Paul Julius Möbius (1853-1907). Both unilateral and bilateral nerve deficits can be observed. In principle, the disease does not progress. The incidence is about 0.002%, i.e. only 1 in 5000 newborns is affected.[19] The prevalence is estimated at about 1 in 500000.[20]

The gender ratio is given between 4:1, with women being the majority affected, and 1:3.[21,22] A connection with cocaine abuse and the therapy with the beta-blocker misoprostol during pregnancy is very likely.[23,24] The diagnosis of Möbius Syndrome is based on clinical evaluation and the CLUFT Grading System.[25] Accordingly, abnormalities of the cranial nerves, the upper and lower extremities, facial structures and the thorax are recorded and assessed according to their severity. Apart from clinical criteria, Möbius syndrome also manifests itself on the genetic level, e.g. through de novo mutations.[26] Such mutations cannot be classically detected in previous generations.

Furthermore, the Möbius syndrome and autistic disorders are less common than originally thought.[27] Problems in social interaction seem to become more pronounced with increasing age.

It should be emphasized that plastic-surgical functional reconstruction is also possible in these cases. Interestingly, the free gracilis muscle transplantation with connection to the masticatory nerve (N. massetericus) was initially performed in patients with Möbius syndrome.[28] The results were so convincing that the N. massetericus became increasingly relevant as a donor nerve for other patient groups with facial nerve palsy. In addition, different treatment options can be chosen depending on the severity of the disease. In cases of bilateral agenesia of the muscles responsible for the smile, the transfer of a thigh muscle (M. gracilis) to both halves of the face with microsurgical connection, e.g. to the masticatory nerve, is the method of choice. This therapeutic procedure enables a more symmetrical and pronounced smile.[29]

Sources:

[1] Peitersen E. Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002(549):4–30. PubMed PMID: 12482166.

[2] Devriese PP, Schumacher T, Scheide A, Jongh RH de, Houtkooper JM. Incidence, prognosis and recovery of Bell's palsy. A survey of about 1000 patients (1974-1983). Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1990;15(1):15–27. PubMed PMID: 2323075.

[3] Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Sawa H, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y. Quantitation of varicella-zoster virus DNA in patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome and zoster sine herpete. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(8):2856–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.8.2856-2859.2001. PubMed PMID: 11474003.

[4] Hauser WA, Karnes WE, Annis J, Kurland LT. Incidence and prognosis of Bell's palsy in the population of Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 1971;46(4):258–64. PubMed PMID: 5573820.

[5] Katusic SK, Beard CM, Wiederholt WC, Bergstralh EJ, Kurland LT. Incidence, clinical features, and prognosis in Bell's palsy, Rochester, Minnesota, 1968-1982. Ann Neurol. 1986;20(5):622–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200511. PubMed PMID: 3789675.

[6] Morris AM, Deeks SL, Hill MD, Midroni G, Goldstein WC, Mazzulli T, et al. Annualized incidence and spectrum of illness from an outbreak investigation of Bell's palsy. Neuroepidemiology. 2002;21(5):255–61. PubMed PMID: 12207155.

[7] Rowlands S, Hooper R, Hughes R, Burney P. The epidemiology and treatment of Bell's palsy in the UK. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9(1):63–7. PubMed PMID: 11784378.

[8] May M, Hardin WB, Sullivan J, Wette R. Natural history of bell's palsy: the salivary flow test and other prognostic indicators. Laryngoscope. 1976;86(5):704–12. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197605000-00011. PubMed PMID: 778512.

[9] Park HW, Watkins AL. Facial paralysis; analysis of 500 cases. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1949;30(12):749–62. PubMed PMID: 15399425.

[10] Prescott CA. Idiopathic facial nerve palsy (the effect of treatment with steroids). J Laryngol Otol. 1988;102(5):403–7. PubMed PMID: 3397632.

[11] Graeme E Glass, Bell’s palsy: a summary of current evidence and referral algorithm, Family Practice, 2014, Vol. 31, No. 6, 631–642

[12] Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, Morrison JM, Smith BH, McKinstry B, Davenport RJ, Vale LD, Clarkson JE, Hammersley V, Hayavi S, McAteer A, Stewart K, Daly F. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell's palsy. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1598-1607.

[13] Engström M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, Axelsson S, Pitkäranta A, Hultcrantz M, Kanerva M, Hanner P, Jonsson L. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell's palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:993-1000.

[14] Gagyor I, Madhok VB, Daly F, Somasundara D, Sullivan M, Gammie F, Sullivan F. Antiviral treatment for Bell ́s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015;5:CD001869.

[15] C. Sweeney, D. Gilden: Ramsay Hunt syndrome. In: Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry (J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.) August 2001, Band 71, Nummer 2, S. 149–154, doi:10.1136/jnnp.71.2.149.

[16] Koch M, Zenk J, Iro H. Long-term results of morbidity after parotid gland surgery in benign disease. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(4):724–30

[17] Eviston TJ, Yabe TE, Gupta R, Ebrahimi A, Clark JR. Parotidectomy: surgery in evolution. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86(3):193–9

[18] Picciolini O, Porro M, Cattaneo E, Castelletti S, Masera G, Mosca F, Bedeschi MF. Moebius syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, management and early intervention. Ital J Pediatr. 2016 Jun 3;42(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s13052-016-0256-5. PMID: 27260152; PMCID: PMC4893276.

[19] Verzijl HT, van der Zwaag B, Cruysberg JR, Padberg GW. Möbius syndrome redefined: a syndrome of rhomben-cephalic maldevelopment. Neurology. 2003 Aug 12;61(3):327-33. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000076484.91275.cd. PMID: 12913192.

[20] Herrera C, Mendieta P, Muzzio L. Reporte de caso clínico: síndrome de moebius. Rev Med FCM‐UCSG. 2010;16(3):237‐242.

[21] Strömland K, Sjögreen L, Miller M, Gillberg C, Wentz E, Johansson M, Nylén O, Danielsson A, Jacobsson C, An-dersson J, Fernell E. Mobius sequence--a Swedish multidiscipline study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2002;6(1):35-45. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2001.0540. PMID: 11993954.

[22] Pedersen LK, Maimburg RD, Hertz JM, Gjørup H, Pedersen TK, Møller-Madsen B, Østergaard JR. Moebius se-quence -a multidisciplinary clinical approach. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017 Jan 6;12(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0559-z. PMID: 28061881; PMCID: PMC5217236.

[23] Puvabanditsin S, Garrow E, Augustin G, Titapiwatanakul R, Kuniyoshi KM. Poland-Möbius syndrome and cocaine abuse: a relook at vascular etiology. Pediatr Neurol. 2005 Apr;32(4):285-7. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.11.011. PMID: 15797189.

[24] Ventura BV, Miller MT, Danda D, Carta A, Brandt CT, Ventura LO. Profile of ocular and systemic characteristics in Möbius sequence patients from Brazil and Italy. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2012 June; 75( 3 ): 202-6. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27492012000300011.

[25] Abramson DL, Cohen MM Jr, Mulliken JB. Möbius syndrome: classification and grading system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998 Sep;102(4):961-7. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199809040-00004. PMID: 9734409.

[26] Tomas-Roca L, Tsaalbi-Shtylik A, Jansen JG, Singh MK, Epstein JA, Altunoglu U, Verzijl H, Soria L, van Beusekom E, Roscioli T, Iqbal Z, Gilissen C, Hoischen A, de Brouwer APM, Erasmus C, Schubert D, Brunner H, Pérez Aytés A, Marin F, Aroca P, Kayserili H, Carta A, de Wind N, Padberg GW, van Bokhoven H. De novo mutations in PLXND1 and REV3L cause Möbius syndrome. Nat Commun. 2015 Jun 12;6:7199. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8199. PMID: 26068067; PMCID: PMC4648025.

[27] Briegel W, Schimek M, Kamp-Becker I. Moebius sequence and autism spectrum disorders--less frequently associated than formerly thought. Res Dev Disabil. 2010 Nov-Dec;31(6):1462-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.06.012. PMID: 20621443.

[28] Morales-Chávez M, Ortiz-Rincones MA, Suárez-Gorrin F. Surgical techniques for smile restoration in patients with Möbius syndrome. J Clin Exp Dent. 2013 Oct 1;5(4):e203-7. doi: 10.4317/jced.51116. PMID: 24455082; PMCID: PMC3892243.

[29] Roy M, Klar E, Ho ES, Zuker RM, Borschel GH. Segmental Gracilis Muscle Transplantation for Midfacial Ani-mation in Möbius Syndrome: A 29-Year Experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Mar;143(3):581e-591e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005368. PMID: 30817662.